Tiong Bahru HIP Voting Failure: A Warning Sign for VERS Implementation

The recent Home Improvement Programme (HIP) voting failure in two Tiong Bahru blocks has sent ripples through Singapore’s public housing community, revealing critical challenges that could significantly impact the upcoming Voluntary Early Redevelopment Scheme (VERS). This incident, where residents narrowly rejected essential upgrade works, offers valuable lessons about community engagement, communication transparency, and the complexities of securing resident buy-in for major housing initiatives.

🏘️ Will VERS Succeed?

Lessons from Tiong Bahru HIP Failure & Pine Ville SERS

The problem:

• 25% didn't vote at all

• Vague cost information

• Quality concerns

• "Might delay VERS later"

The catch:

• Fresh 99-year lease ✓

• Modern facilities ✓

• BUT residents paid $31k-$100k+

• Not the "windfall" SERS used to be

• It's voluntary - residents can say no

• Flats will be 70+ years old - lower compensation

• Estimated cost: $200k+ per household

• Needs majority votes - if 25% don't vote, scheme fails

• Less redevelopment value than prime SERS sites

Tell residents EXACT costs upfront - no "blank checks"

Subsidies for elderly & lower-income residents

Solve the absentee landlord problem

Pilot 2-3 favorable sites first, build confidence

Don't make voting threshold too high (or too low)

The Tiong Bahru HIP Vote: What Happened?

In November 2024, two aging HDB blocks in Tiong Bahru failed to achieve the required voting threshold for HIP approval by a narrow margin. According to forum discussions, approximately 25% of residents did not participate in the voting process at all, contributing to the failure to meet the acceptance threshold.

The rejection was particularly striking given that the HIP would have provided much-needed upgrades including lift installations and general improvements to the aging blocks. Residents who voted against the proposal cited several concerns:

1. Vague Communication and Cost Uncertainty

Multiple residents reported that the information provided by authorities was frustratingly unclear about costs. One resident described the communication as having “a hint of arrogance,” feeling like authorities were saying they should accept whatever costs would be charged later without transparent details upfront. The lack of clarity about which residents would bear costs and which wouldn’t added to the confusion and distrust.

2. Quality Concerns

Several residents expressed skepticism about the quality of HIP works based on previous experiences in their estates. Reports of lifts becoming slower and bumpier after upgrades, extended construction periods, and concerns about contractor quality influenced voting decisions. With material costs having doubled since COVID-19, residents worried about receiving substandard work.

3. Impact on Rental Properties

A significant factor was the number of units owned by landlords who were not residing in Singapore. These absentee owners couldn’t easily participate in voting or assess the benefits, contributing to low participation rates. Some residents noted that HIP works might force tenants to relocate temporarily, creating additional complications for rental property owners.

4. VERS Timing Concerns

Perhaps most tellingly, some residents noted that conducting HIP now might delay potential VERS selection for Tiong Bahru, which has many old HDB blocks that could only benefit from VERS in the future. This created a strategic dilemma for homeowners weighing short-term improvements against long-term redevelopment prospects.

Why This Matters for VERS

The Tiong Bahru HIP voting failure should serve as a wake-up call for policymakers preparing to roll out VERS in the early 2030s. Here’s why:

1. Higher Stakes, Higher Resistance

If residents struggled to achieve consensus on a relatively straightforward upgrade programme, the challenges with VERS will be exponentially greater. VERS involves:

- Permanent displacement from existing homes

- Significant financial commitments (potentially $31,000 to $200,000+ in top-ups based on AMK SERS precedents)

- Irreversible decisions about 70+ year-old properties

- Complex voting mechanisms requiring majority support

The voting threshold for VERS has not yet been officially announced, but it will likely require substantial majority support. If 25% of residents can’t even be bothered to vote on HIP, how will authorities secure the necessary participation and approval rates for VERS?

2. Communication and Trust Deficit

The Tiong Bahru HIP experience revealed a critical breakdown in communication. Residents felt they were being asked for a “blank check” without adequate information. For VERS to succeed, authorities must provide:

- Crystal-clear financial projections: Exact compensation amounts, replacement flat costs, and out-of-pocket expenses

- Transparent timelines: When residents will need to move, how long redevelopment will take

- Detailed benefit explanations: What residents gain versus what they sacrifice

- Quality assurances: Guarantees about replacement flat standards and amenities

The second-round voting mentioned by some Tiong Bahru residents, where authorities provided better information after initial feedback, shows that improved communication can change outcomes. However, VERS won’t have the luxury of multiple voting rounds.

3. The Absentee Owner Challenge

Tiong Bahru’s experience with rental properties highlights a significant VERS challenge. Many older estates have:

- High proportions of rental units owned by landlords living elsewhere

- Investment properties held by elderly owners in nursing homes

- Properties managed by children of deceased original owners

For VERS to proceed, these stakeholders must be engaged and motivated to participate. Unlike HIP, where opting out means the status quo continues, VERS requires active participation from a supermajority. Any scheme that allows absentee owners to simply ignore voting will fail.

4. Competing Incentives and Strategic Behavior

Some Tiong Bahru residents voted against HIP because they believed doing so might accelerate VERS selection. This reveals that residents will make strategic calculations about their votes based on perceived long-term benefits.

For VERS, similar dynamics will emerge:

- Older residents may oppose VERS if they don’t want the disruption in their remaining years

- Younger homeowners may support VERS for the fresh 99-year lease despite costs

- Investors may calculate based on potential rental income disruption versus property value gains

- Multi-generational families may struggle to agree on whether participation benefits their situation

Authorities must design VERS to align incentives across these diverse stakeholder groups, or risk the same fragmentation that doomed Tiong Bahru’s HIP vote.

5. The “Gentrification Gap” Problem

Tiong Bahru is notably different from typical aging estates—it’s a gentrified, hipster neighborhood with high rental rates (up 60% over three years) and strong demand despite lease decay. Yet even with these advantages, residents couldn’t agree on upgrades.

Most estates facing VERS won’t have Tiong Bahru’s cache. They’ll have:

- Lower property values due to lease decay

- Less affluent residents with lower financial capacity for top-ups

- Weaker market demand making the cost-benefit analysis less favorable

- Greater proportions of elderly residents on fixed incomes

If Tiong Bahru struggled, estates like Queenstown, Toa Payoh, or older parts of Ang Mo Kio, Bedok, and Tampines may face even steeper challenges achieving VERS consensus.

The Pine Ville Contrast: When SERS Works (But at What Cost?)

The Pine Ville @ AMK SERS project, announced in April 2022 for Blocks 562-565 Ang Mo Kio Avenue 3, offers a stark contrast to Tiong Bahru’s voluntary voting failure. Under SERS, the 606 affected households had no choice—participation was mandatory once their blocks were selected.

Benefits Pine Ville Residents Received:

1. Fresh 99-Year Lease in Mature Estate

The most significant benefit was receiving brand new flats with fresh 99-year leases in the same mature Ang Mo Kio estate. This addressed lease decay concerns comprehensively—their old flats were aging, but they received new homes that would last their lifetimes and beyond.

2. Enhanced Connectivity

Pine Ville’s location will benefit from the upcoming Cross Island Line, with Tavistock (CR10) and Teck Ghee (CR12) MRT stations expected by 2029/2030. This represented a major connectivity upgrade for residents.

3. Modern Amenities and Facilities

The new development includes:

- Comprehensive internal amenities (shops, eating houses, minimarts, childcare)

- Superior facilities compared to their 40+ year-old blocks

- Access to Ang Mo Kio’s extensive mature estate amenities (AMK Hub, Jubilee Square, markets, schools, parks)

4. Standard MOP and Resale Flexibility

Unlike new “Plus” BTOs in the area, Pine Ville residents benefit from the standard 5-year Minimum Occupation Period with no subsidy clawback restrictions or limitations on renting out entire units. The earliest resale date is estimated at Q3 2032, and some analysts project that well-located 4-room units could reach $1 million by then due to their fresh leases and CRL connectivity.

5. Community Participation

Residents were consulted on naming and facility design. After submitting preferences in April 2023, the estate was officially named “Pine Ville @ AMK” in September 2023, giving residents some ownership over their new community.

The Hidden Costs and Challenges:

However, the Pine Ville SERS was far from the windfall that earlier SERS exercises represented. This project revealed a concerning shift in how SERS operates:

1. Significant Out-of-Pocket Costs

Unlike traditional SERS where residents typically gained money, AMK SERS residents faced substantial top-ups:

- Elderly residents needed to pay between $31,100 to $100,000+ for like-for-like replacements

- 4-room units ranged from approximately $500,000 to $700,000+ depending on specifications

- Compensation was based on 2022 market value plus only $17,300-$19,400 in relocation expenses

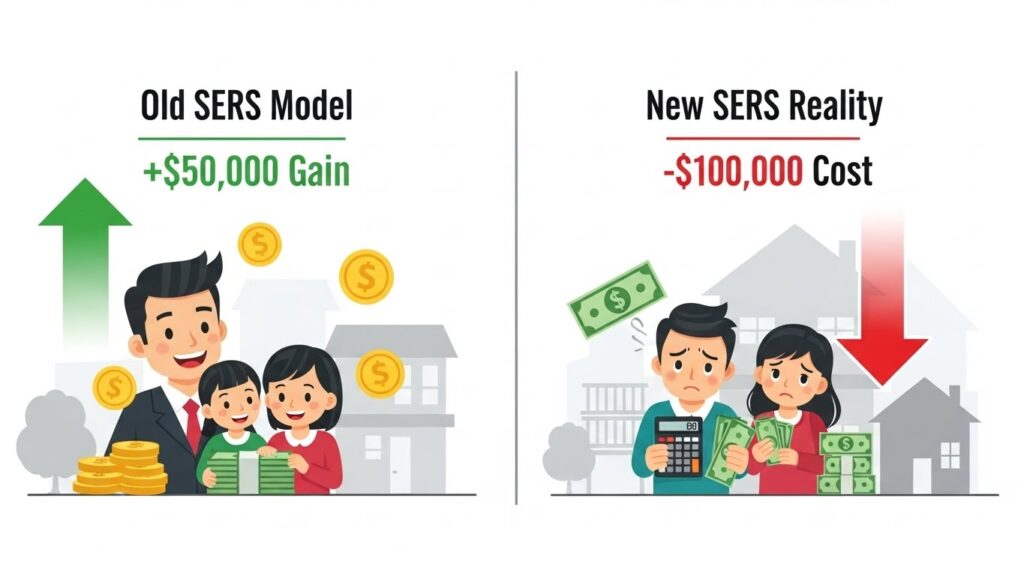

Traditional SERS Model:

- Old Flat Value: $300,000

- Compensation: $400,000

- Replacement Cost: $350,000

- Net Result: +$50,000 (residents GAINED money)

AMK SERS Reality:

- Old Flat Value: $400,000

- Compensation: $400,000

- Replacement Cost: $500,000

- Net Result: -$100,000 (residents PAID money)

2. Emotional and Social Displacement

Despite the physical improvements, Pine Ville residents experienced:

- Loss of longtime homes and communities (many had lived there since 1979)

- Breaking of established neighborhood bonds and support networks

- The bittersweet reality that “progress often comes with trade-offs—some visible in the skyline, others felt only in the heart”

3. Financial Strain on Vulnerable Groups

The requirement for substantial top-ups hit hardest among:

- Elderly residents on fixed incomes with insufficient savings

- Lower-income households who struggled to afford market-rate replacement flats

- Multi-generational families needing larger or multiple units

4. Market Uncertainty

While some optimistic projections suggest strong resale potential, risks remain:

- 1,068 units entering resale market post-2032 could suppress prices

- Maximum 93 sqm 4-room units lag behind typical million-dollar HDBs (usually 120+ sqm)

- 10-year MOPs for some units delay market liquidity

- Future value depends heavily on CRL completion and economic conditions

Critical Lessons for VERS Implementation

The Tiong Bahru HIP failure and Pine Ville SERS experience together paint a challenging picture for VERS. Here are the critical lessons:

1. Build Trust Through Radical Transparency

Future VERS communications must avoid the mistakes of Tiong Bahru HIP. Authorities need to:

- Provide detailed financial models showing exact costs for different household types

- Offer personalized impact assessments so each household knows their situation

- Share quality guarantees and contractor selection processes upfront

- Create accessible information channels with responsive feedback mechanisms

The “blank check” approach that doomed Tiong Bahru’s HIP will be fatal for VERS.

2. Address the Affordability Gap

If Pine Ville residents struggled with $31,000-$100,000+ top-ups, and VERS may require even more, authorities must:

- Develop graduated subsidy schemes for elderly and lower-income residents

- Create flexible financing options beyond traditional housing loans

- Consider means-tested grants to prevent financial hardship

- Offer alternative housing solutions for those who genuinely cannot afford participation

A VERS scheme that prices out 30-40% of residents due to affordability will never achieve voting thresholds.

3. Solve the Absentee Owner Problem

VERS cannot succeed if 25% of stakeholders simply don’t participate. Solutions might include:

- Mandatory voting participation with legal consequences for non-participation

- Proxy voting systems for landlords and overseas owners

- Financial incentives for early voting or penalties for non-voting

- Deemed consent after extensive outreach efforts (controversial but potentially necessary)

4. Set Realistic Voting Thresholds

If the voting threshold is too high (e.g., 90% support required), VERS will rarely succeed. If too low (e.g., 51%), minority residents will feel steamrolled. Authorities must:

- Study international en-bloc precedents to identify workable thresholds

- Consider multi-tiered thresholds (lower for first vote, higher for final approval)

- Allow for multiple voting rounds with improved information

- Ensure threshold accounts for non-participation patterns

5. Stagger Implementation to Build Confidence

Rather than launching VERS widely, authorities should:

- Begin with 2-3 pilot sites with most favorable conditions

- Document and share detailed case studies from these pilots

- Adjust framework based on lessons learned

- Gradually expand to more challenging estates once model is proven

The government has indicated VERS will start in the first half of the 2030s with limited precincts, which aligns with this approach. However, these pilots must genuinely succeed, not just proceed with disgruntled participants.

6. Integrate with HIP II Strategically

The concern that HIP might delay VERS selection reveals poor coordination between schemes. Instead:

- Clearly communicate how HIP II and VERS interact for each estate

- Use HIP II as a bridge to maintain livability until VERS

- Don’t force residents to choose between short-term improvement and long-term redevelopment

- Design HIP II to enhance VERS prospects rather than compete with them

The Broader Housing Policy Challenge

Both Tiong Bahru’s HIP failure and Pine Ville’s mixed SERS success reveal a fundamental tension in Singapore’s aging housing policy:

Residents want:

- Free or low-cost improvements to aging homes

- Fresh leases without major financial sacrifice

- Choice and autonomy in decisions affecting their homes

- Fair compensation recognizing their decades of ownership

Government faces:

- Fiscal sustainability concerns with massive redevelopment costs

- Limited land for replacement housing

- Need to balance competing demands across generations

- Reality that not all sites have redevelopment upside

The result:

- Traditional generous SERS is ending (Pine Ville likely the last)

- VERS will require significant resident financial contribution

- But voluntary schemes requiring majority support may fail without generous terms

- Creating a potential gridlock where aging estates can’t achieve consensus for redevelopment

Recommendations for Policymakers

To break this potential gridlock, policymakers should consider:

Short-term (Before 2030):

- Conduct extensive pre-VERS consultations with residents in candidate estates to understand concerns and refine framework

- Develop detailed VERS financial models showing impact on different household profiles

- Create pilot engagement programs in 2-3 estates to test communication strategies

- Establish VERS education initiatives to build understanding of the scheme

- Research international best practices from similar voluntary redevelopment schemes

Medium-term (2030-2035):

- Launch VERS with most favorable 2-3 sites where strong community support exists

- Provide generous subsidies for pilot sites to ensure success and build confidence

- Document and widely share detailed case studies from pilot implementations

- Iterate on framework based on pilot learnings before broader rollout

- Establish independent oversight to ensure transparency and fair treatment

Long-term (2035+):

- Gradually expand VERS to additional estates based on proven model

- Maintain flexibility to adjust terms based on each estate’s unique circumstances

- Consider differentiated approaches for estates with varying financial capacity

- Integrate VERS with comprehensive estate renewal strategies including transport, amenities

- Continuously monitor and adjust to maintain public confidence

The narrow failure of Tiong Bahru's HIP vote may seem like a minor incident—just two blocks rejecting upgrade works. But it's a canary in the coal mine for VERS implementation.

The experience reveals that even straightforward, beneficial upgrades can fail when:

- Communication is poor and trust is low

- Costs are vague and quality uncertain

- Residents have competing strategic incentives

- Participation rates are inadequate

VERS faces all these challenges magnified by much higher stakes. The Pine Ville SERS experience shows that even mandatory schemes with government selection create financial strain and mixed outcomes when costs are shifted to residents.

For VERS to succeed, authorities cannot simply rely on residents being rational actors who will obviously support getting fresh 99-year leases. They must:

- Build genuine trust through radical transparency and responsive engagement

- Address affordability so financial constraints don’t prevent willing participation

- Solve participation problems so voting thresholds can actually be achieved

- Set realistic expectations about costs and benefits for different groups

- Learn from pilots before broad implementation

The alternative is a future where aging estates can’t achieve VERS consensus, leading to a growing stock of lease-decayed flats that residents can neither improve (HIP rejected) nor replace (VERS failed to achieve voting threshold). This would create pockets of declining housing quality and value in Singapore’s most mature estates—precisely the outcome both HIP and VERS are designed to prevent.

The time to address these challenges is now, during the framework development phase, not after the first VERS votes fail and residents lose confidence in the scheme. Tiong Bahru’s HIP failure and Pine Ville’s bittersweet SERS success offer valuable lessons—the question is whether policymakers will heed them.

About 563amk.com

563amk.com is run by The Pine Ville Cat, a professional void deck observer with over 7 years of napping experience in the Ang Mo Kio SERS blocks. All analysis is based on publicly available information, extensive void deck surveillance, and the occasional overheard conversation between property agents. For serious housing decisions, please consult actual humans with property licenses. For napping spot recommendations, The Pine Ville Cat is available for consultation (payment in tuna accepted).

Disclaimer: The Voluntary Early Redevelopment Scheme framework is still under development, and details may change. This analysis is based on current information and official statements from the Ministry of National Development.